Down Is Up discusses music that falls slightly under the radar of our usual coverage: demos, self-releases, and output from small or overlooked communities. Today, Jenn Pelly speaks with Alexander Heir, a visual artist who has helped to shape the aesthetic of contemporary punk culture in NYC and beyond. His book, Death Is Not the End, is out now via Sacred Bones.

All works by Alexander Heir

Alexander Heir's tiny bedroom-studio in Brooklyn looks like a Halloween discount-store dumpster on November 1. Dollar-store skull-faced totem poles, gnarly temporary tattoo sheets, paintings plucked from the trash and made to look morbid—from ceiling to floor. "I'm drawn to cheesy, poorly-drawn skulls," the 30-year-old Heir says gleefully, "so it defaults to Halloween." Heir has developed a reputation for this among friends, as I learn when inquiring about the tiny bones sprinkled around the room, which some pals collected for him at NYC wing nights. Another friend was working at a restaurant when inspiration struck. "He was like, 'Hey, I have these chicken feet, you want them?" They are now chicken-foot necklaces. "It would just be trash," Heir says with a native New Jersey accent, "but instead it becomes a precious object." Most prominent, in the studio, is a massive skeleton lawn ornament, the kind you only see in the suburbs, placed above his workspace. "It was sitting in a friend's parents' garage on Long Island, and he was like, 'Do you want this?' I don't really have space, but I can't say no."

This might sound like mere hoarding, but it's purposeful: The setting inspires the dark yet humorous spirit of his work as an illustrator, painter, and designer, which has helped to shape the aesthetic of contemporary underground punk. The Xeroxed show flyers, album art, and T-shirt designs (for his apparel company, Death/Traitors) are equal parts Pushead macabre, Eastern mysiticism, and occultish lore—all documented in the just-released Death Is Not the End, his first book from Sacred Bones. Heir, also a musician, is an effective multi-tasker. When we spoke last month, he was at work on a last-minute banner for a friend's band, who were participating in a Satanic Black Mass reenactment at Harvard. "This is the kind of shit I do all day," he says, staring intently at the screen. On this spring day, Heir is clad in a bleached, teared-up "Nuke York" T-shirt; his hair is cut close, save for a tiny braid with a skull at the end. Of his myriad tattoos, I notice an anarchy symbol with Mickey Mouse ears.

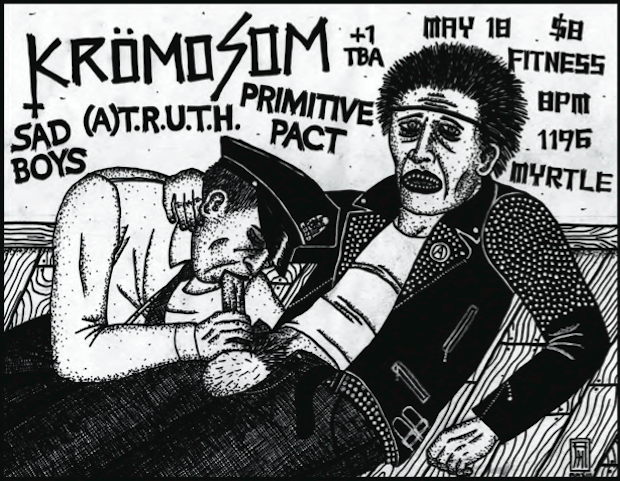

Heir's artistic imagination runs deep. Recurring motifs are skulls and grim reapers, but you'll also find a fair share of tombstones, spiders, spikes, intestines, mutants of all nature, decapitated humans with disembodied grins. Death Is Not the End includes a number of anatomical studies and ripped-apart faces—inspired by surveillance culture—and, naturally, a cop sucking a punk's dick:

For all the death, fear, and rage that coarses through Heir's work, he is extremely amicable and outgoing. His aesthetic has been tied to the likes of Hoax, Modern Life Is War, the Men, Destruction Unit, Iceage, and Total Control; when we meet, he shows me an in-process design for the rapper Antwon, and an upcoming collaboration with Rawten to benefit Schools for Chiapas. But the mutated raw punk of New York's underground is where his primary collaborators dwell. Not unexpectedly for someone involved with the NYC punk scene—filled with bands that seem to actively resist outside attention—Heir is open about his initial reservations in speaking with me. He admits he's more organized than a lot of his comrades: "I think I'm the only guy in the punk scene who knows how to use Photoshop," Heir says, laughing. But that staunch underground rooting makes his work feel like a rare look into something hidden far below the surface, a twisted glimpse I wouldn't take for granted.

Heir and I spoke about his formative experiences with art and punk, his interests in occultism and anatomical surgical guides, the political streak that runs through his work, and more.

Pitchfork: You're from New Jersey. What was your introduction to punk there like?

AH: I started listening to punk around 1996. At that point, Rancid and Green Day were on the radio—punk was in the mainstream. I guess I heard them and Offspring on K-Rock or MTV or whatever. And I was like, "Woah, what is this?" Beyond that, there was a thriving local scene of hardcore and ska and pop-punk. I was the only "punk"-punk kid at my high school—I had a mohawk and a studded jacket. I was like, the Freak.

Pitchfork: What's the most important thing punk taught you as a kid that you carry forward as an artist?

AH: Punk is a gateway to seeing the world for what it is. When you're 15, who else is going to tell you, "Yo, the police are actually really bad. The government's actually bad. Your country is doing all this fucked up stuff." And all these other ideas that some people never discover. People search out punk or subcultures because they don't feel connected to mainstream culture, which is capitalism, which is, like, The Matrix. So punk is a way to escape The Matrix.

I always got along with my parents and was in honors classes and all that shit. But I saw how anyone who's different from the norm is treated differently by their peers and authoriy. Punk teaches you empathy at a really young age. I was never super political, but the idea of being aware always resonated. Like, "Woah, there's really important stuff happening, and we're just living in this bubble." That always bothered me, especially being from New Jersey—who gives a fuck about the soccer team or your Juicy Couture or whatever, when there are children out there making shoes in factories. When you're young and first discovering that, you're like, "Oh god, I've been lied to, what the fuck?" That sentiment never leaves you.

The word "punk" in itself is amazing, but it can hold you back—because you're always like, "Is this punk?" It has an obsession with its own past. It's great that it's become an established culture with a tradition to follow, but when it prevents you from trying new things, that's not really the spirit of what it should be. Everyone wants to protect their own little community. It's easy to look at older bands like Discharge and hold them up on this pedestal, but it's not 1984 anymore. The world isn't the same. It's weird to hold yourself to those standards.

I go through moments of life where I'm like, "Fuck it, I need to sell out and make money because I need to go buy a farm because fuck everything else, the world is about to end." When all the bees are gone and you have to pay $100 for a gallon of water, who cares about your cred? You just need canned goods.

Pitchfork: Your father is a painter. Do you remember your earliest experiences being exposed to visual art?

AH: I was always exposed to art—I was going to the museums when I was a baby. Even before punk, I learned that art reveals truth. The first art experience I can recall was with this sculptor Calder, who does these geometric mobiles. There was an installation at the Whitney—these weird little circus pieces made out of trash and found objects, and they would move. I remember being really young and staring at this stuff. It was the marriage of that with discovering Pushead and Misfits art, around the time I was 12 or 13.

Pitchfork: Do you remember the first time you drew a skull?

AH: I was always doodling as a kid, and I've always been attracted to the darker side of stuff. My mom has a book of my earliest drawings from kindergarten—crayon monster drawings. I got in trouble once in grade school because we had to draw lambs, and I drew my lamb with a gun holster. [laughs] Pushead was a huge influence of mine, and you always start off copying the people you like. That was my starting goal: "I want to draw a skull that I think looks great." I drew it endlessly, figuring out proportions. It eventually became a symbol of my work or something. I try not to rely on it, but it always comes back. "What do I want to see in this? Put a skull on it!"

Pitchfork: Occult imagery and symbolism also figure heavily into your aesthetic.

AH: I first started using the "666" with Death Traitors as a middle-finger to all these Christian people and the insane religious right. In New York, you can wear a "666" and it's whatever. But people will write to me from the Midwest and be like, "Man, I wear this and people just bug out." It really bums people out and I think that's good. To a really religious person, a "666" or an occult image really means something. You could argue that that's actual magic.

Pitchfork: I read that you're influenced by the aesthetic of Russian criminal tattoos, too. How'd you find that and what does it mean for your work?

AH: I am always draw to the beautiful-ugly. Things that are not quite perfect. Or wrong, or off, but still awesome. That's what my room is filled with. It's why I love shitty Halloween costumes—a poorly drawn skull that just looks so good. It's the same with punk music—it's supposed to sound dirty. When it's recorded really well and clean, with talented musicians, it's not the same thing. When I first started drawing, it frustrated me: "I can't sit down and perfectly render something, I can't draw realistically." When I started really working, I realized that's not really important. There's a fine balance, but anatomical perfection isn't necessarily the epitome of art.

Pitchfork: I read that you are also interested in anatomical surgical guides.

AH: My interest in skulls grew out of my interest in anatomy. A lot of the stuff I do with violence is as much about the actual action as it is about me wanting an excuse to draw some anatomy—wanting to draw a guy ripped open, so I'll throw him on a stake.

Japanese woodcut artists are my favorite. Yoshi Toshi's stuff is so graphic and simplified. I first started discovering that stuff in high school. I had always been into Gundam robots and Dragon Ball—I was never a hardcore anime fan, but that style interested me. I took Japanese in high school for four years, so through that, and my interest in art, I discovered all this stuff and it blew me away. It's funny how punks are now obsessed with Japan—I mean, GISM is one of the best bands of all time, but there is more access to all of it now.

Pitchfork: Can you tell me about the cover of the book and the title?

AH: It's a theme I've been riffing on for a while—the split face, duality. It's a semi self-portrait. It embodies everything: the skull, anatomy, the occult, the worlds of reality and imagination. When I was in school I had a label called Death Attack and the first shirt I printed was a photo of a door; it said, "Death is not the end."

Pitchfork: There are a lot of drawings of cops in compromised positions. Have any personal experiences contributed to your extreme disdain of the police?

AH: A lot of it is instant gratification. When you see a flyer, who's not gonna love something bad happening to a cop? The police officer in my work is a representation of state force—the physical embodiment of that spirit of oppression. But I'm a white guy. I don't really have a right to complain about the police on a personal level. I don't get racially profiled; I don't get harassed. Again, it's about general empathy, and what the police represent as an arm of the overlords. The worst thing for me is this constant sense of surveillance and fear. When you leave New York and go overseas, there isn't such a police state. It sucks that that should be a nice surprise instead of the way you should demand to live everyday.

Pitchfork: There's a piece at the very beginning of the book of a person ripped apart and being examined—it immediately made me think of the surveillance culture.

AH: When I finished that, I was like, "Woah, I'm starting to figure stuff out. This is what I should be doing." I'm kind of a news junkie. I'm always reading about that stuff. It's crazy to me that not everyone is making work about that. A lot of the stuff I do comes across as political, but I think about it like: "I'm just a regular ass person, and this shit is crazy." Why isn't everyone else freaking out about this?!? Why isn't everyone else demanding humanity, and to not be ruled by the reptiles?

Maybe I should just get a bunch of money and move to a farm.

Pitchfork: Can you describe the role of the grim reaper in your work?

AH: The acknowledgement of death is a big theme. And the acknowledgment of that in the face of advertisements and pop culture, and everything people always try to shove in your face—it's exciting. Instruments of torture and execution have always interested me as representation of the terrible things that humanity does. A guillotine is a portal to death; it's the physical embodiment of that change in a really gruesome, unnatural way. Some guillotines—but even more so, iron maidens—are so beautifully adorned and designed, it's bizarre. It makes me think of modern day advertising. The shiny packaging on some food, which is essentially poison.

Pitchfork: There are a lot of violent images in the book—the sacrified baby, or peoples' heads chopped off—but in general, it seems like your work opposes violence. There is also this visible call for justice and freedom.

AH: I'm a very peaceful person. But I'm drawn to these images of violence. Some of it is the excitement and shock value, but a lot of the pieces have humor in them as well, even if it's violent. That one of the baby was for a New Year's show. Everyone always does the New Year's baby. What if it's the New Year's baby getting sacrificed? It's almost the inverse of the shiny-colored cigarettes—which look nice, but will kill you. This stuff looks really bad for you, but it's actually not. Punks always try to look so scary, like we're tough, but the punks I know are the only people I trust in this world. They're some of the sweetest and most empathetic people I know.

I do wonder if one day I'll ever be settled enough that I'll just paint flowers all day.

Pitchfork: Have you ever painted a flower?

AH: One piece I'm working on is this creepy head, surrounded by flowers.

Pitchfork: The 2011 "You Are Your Own Master" piece captures the essence of your work and has seemed to resonate with a lot of people.

AH: That was definitely a watershed moment. At the time I was reading a lot about Satanic ideas, but also [1971's] Be Here Now and stuff like that. The phrase can take on so many meanings, from the surveillance state to religion to incarceration. It was initially designed because I had been throwing stickers in with my orders for free, and I thought, I'll make my own photocopied propaganda piece and put it in there.

Pitchfork: To what degree were 1970s British punk aesthetics inspiring to you with Death/Traitors?

AH: When I first started making T-shirts, one of my biggest influences was Seditionaries and Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood. It showed me that being a punk and being an artist aren't mutually exclusive. At the end of the day, they were both more artists than punks. For me, punk was always about being creative and aware—living outside the constrictions that are given to you—versus a type of rock and roll or a fashion sense. But visually, I do love that stuff. [Pulls out Anarchy T-shirt] This shirt was about freaking people out—"Anarchy on the streets!" It's similar to the "666"... I'm not necessarily a practicing Satanist, but hey, fuck you and fuck your religion.

Pitchfork: What would you say has been the biggest highlight for you as an artist over the past few years?

AH: Getting to design a shirt for The Mob in 2012 was a huge honor, a band from the original wave of anarcho-punk that has influenced me. It was really great getting asked to do the MRR cover, a punk institution. And this book. Last year I had an art show in Barcelona, which was amazing. I'm going to try to do a London residency. Japan is the goal. There are a billion things I'd like to do. As much as punk is about smashing institutions, I can't say I wouldn't want to have a painting hanging in MoMA someday. But who knows if MoMA will even exist in 20 years or if it will be flooded by then? Everything will be below sea level.

Pitchfork: When do you think society is going to collapse?

AH: I always go back and forth between thinking I'm not doing enough to prepare and being like, "Oh, you're just being an insane alarmist." But some pretty serious people say it's coming down the line. It's also a relative question—for some people, society has already collapsed. Realistically, we probably have another 100 years. It's probably not going to be very drastic. It's going to be a slow squeeze, where everyone in the working class struggles. An apple that's not covered in toxins is already like, a luxury item. So, that's just gonna get worse. It's up to you to decide how much to prepare.

This is also something about the duality of my work. I'm driven by stuff that can be very dark and cynical, but I'm a pretty upbeat, cheerful person. You can't let that stuff ruin your well-being. Maybe I'm being naive, but I try to let that stuff inform my work and my worldview without being a paranoid nut. Like a sad clown.

I've worked through all of these influences and tried to create my own language. I want my art to be a gateway into seeing the world in a different light, like punk itself. At the beginning of Death/Traitors, something I thought about was, "How can I make being a thoughtful, empathetic person be sexy?" Because that's real power. You're not going to topple any governments with a painting, but if some kid can see your work, and from that, discover a little bit about themselves or the world—that's the point.