The first proper single of Tupac’s career was "Brenda’s Got a Baby" in 1991, and that’s kind of insane to think about, and it’s insane in two different ways: (1) because of what it is about, and (2) because of what Tupac eventually came to represent in rap.

"Brenda’s Got a Baby" is about an illiterate twelve-year-old girl who gets impregnated by her older cousin, secretly gives birth to the baby on a bathroom floor, puts the baby in a Dumpster, gets kicked out of her house, attempts to become a crack dealer, gets robbed, becomes a prostitute, then gets murdered. It’s as "socially conscious" a rap song as has ever been written.

The singles that followed either replicated the tone (though rarely to such extremes)

or spun in the other direction altogether. Over one very eager stretch of six months in 1993, he released "Holler If Ya Hear Me", a frustration anthem and his very best Public Enemy impersonation, followed by "Keep Ya Head Up", a female empowerment song, followed by "I Get Around", which is about having lots of sex with lots of females. The contradiction was an early indication of the kind of in-the-moment, emotionally reflective artist Tupac was, and would become, and that’s how we get to what Tupac came to represent.

Distilled down to its pith, the entirety of gangsta rap imagery is Tupac; he is the archetypal gangsta rapper, and he has come to stand in for any and all other rappers in the subgenre. That’s an easy claim to make because he, in fact, perfected gangsta rap, but it’s also slightly tricky. He was so convincing in the role that he effectively rendered all other portrayals obsolete, or, worse still, uncool. (Nearly) all of the images we’ve come to associate with gangsta rap are images he presented. And the origination of that version of him was him on "California Love", when Dr. Dre stood back behind him in the Thunderdome and framed his mania, and it was so exciting and obvious when it happened.

♦

"California Love" is a great song. It’s a funky, chirping, fever of noise, the sonic weirdness is boxed in by Roger Troutman’s robo charm, pummeled into acquiescence by Tupac’s fury, and weighed and measured by Dre’s steadiness. All three parts play perfectly together. Examined free of the context of Tupac’s career, it would have lived a perfectly pleasant life, and likely even still managed to become critical to the rap genre.

But it arrived to an almost unfathomably perfect orchestra of circumstance, and so it is endlessly important today, and forever, on earth and in heaven and anywhere else they listen to rap. To wit:

- It was the first song Tupac released when he got out of prison in 1996, and that would’ve been gigantic all by itself. But the insanity surrounding his court case at the time of his sentencing had grown his indestructible gangster myth tenfold, so Tupac getting out of prison was less him getting out of prison and more him rolling away the stone and stepping up out of the tomb.

- It was the first song from his new album, All Eyez on Me, which was coming behind Me Against the World, his most successful album to that point, commercially (it moved more than 3.5 million units) and critically ("Dear Mama"; see page 106).

- It was the first thing he delivered under Death Row, a label that was, at that moment, the biggest and baddest and most overwhelming in rap.

- It was produced by Dr. Dre.

- And his amazing film run from 1992 to 1994 (Juice, Poetic Justice, Above the Rim) stretched his name well beyond the parameters of just rap, and even just music.

You can imagine the sort of fervor that surrounded this song when it dropped. It was his biggest song figuratively, because of its commercial success, but also literally. Up to that point he’d mostly been an insular artist, with ideas and thoughts aimed in specific directions. “California Love” gave him the wide-screen treatment we’d watch the Notorious B.I.G. get later. It was a glimpse at what he was going to do as a proper superstar, and also pointed toward where Puff Daddy would eventually take rap.12

♦

"California Love" was not originally Tupac’s song. There are two conflicting stories on how he nabbed it. One comes from Chris "The Glove" Taylor, who claims he helped produce the track (though he received no credit for it), and the other from Death Row’s cofounder and former CEO Suge Knight, who is like if an angry rhino began morphing into a human and then stopped halfway through and so that’s just how he was stuck.

The parts that they quibble about are the parts you’d expect (Taylor says he helped piece together the track with Dr. Dre at his house, while Knight tells some overly complex story about a stylist wearing a leather suit and that’s where the Mad Max theme for the video came from, or something), but they both agree on one point: It belonged to Dr. Dre before it belonged to Tupac. Taylor says he and Dre made it at Dre’s house during a get-together, and then Tupac showed up and was in the studio so he recorded a verse for it. Knight says that the song had been written for Dre, but since The Chronic had already been out, and since Tupac’s album was on its way, Suge thought the song should go to Tupac. There’s a moment during Suge’s explanation where he basically congratulates himself for not blatantly stealing the whole song by allowing Dre to remain on it, and it’s easy to see how Suge eventually pile-drove Death Row into nothingness.

♦

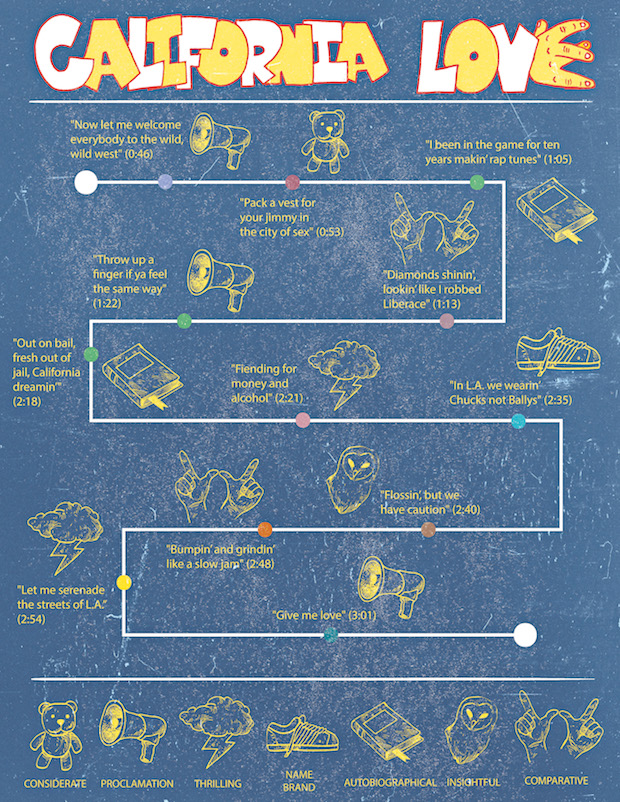

There are thirteen reasons you should visit California and celebrate California, according to Tupac and Dr. Dre in "California Love".

Good Reasons

- Lots of opportunities for sex: If you are in charge of promoting tourism for your state, you should 100 percent include that your state has a higher sex rate per capita than other states, if that happens to be the case.

- Bomb-ass hemp: "Bomb ass" is slang for "very good," and "hemp" is slang for "marijuana." I remember reading this thing about how when you want to add a new word to your vocabulary, you have to use it two times out loud, so I’d recommend that here for you so that you can get comfortable saying this. For example, if your friend’s mother passes away, you might try consoling him or her by commenting on the high quality of the event: "Susan, hi, I just want to say real quick that this is a bomb-ass funeral. Your mother, also bomb-ass, would’ve been pleased."

- Dance floors busy with bodies: "Ecclesiastes assures us . . . that there is a time for every purpose under heaven. A time to laugh . . . and a time to weep. A time to mourn . . . and there is a time to dance." —Kevin Bacon, Footloose. Footloose is so much fun.

- Hoochies, likely screaming: Hoochies who like to scream are better than, say, hoochies who like to stab, or hoochies who like to steal your identity.

- Chucks: This is in reference to the Chuck Taylor Converse. Chucks are timeless.

- Dark sunglasses and khaki suits: This seems a lot like something that a murderer would wear, because it’s difficult to picture a sane person shopping in a store and asking where the khaki-suit section is. But dark sunglasses and khaki suits are always cool.

- Caution: This is from the line "Flossin’, but have caution," and, really, being cautious while flossin’ is smart, and it’s the way I’d floss were I ever in a position to do so. (It’s also probably counterintuitive to the spirit of flossin’. Still, it’s a good reason, just to be safe.)

- The potential to bump and grind like a slow jam: I am a very big fan of bumping and grinding, be it like a slow jam or any other jam, really.

- Bomb beats from Dre: Sure.

- Serenades: Okay.

Roger Troutman’s Zapp band had a very clear influence on G-Funk. Dr. Dre choosing to use him for the hook on “California Love” indicates a new stage in rap: having precedents and heroes and the ability to incorporate them into the new music being made from their seeds. That he was being featured on a song that was connecting gangsta rap with G-Funk for this new thing feels significant, too, as does the fact that this celebration of Cali counterculture was happening while the ground was still vibrating from the police batons and boots that had swung at and stomped on Rodney King. “California Love” was Tupac’s turn as the biggest gangsta rapper in the world. He was dead nine months later.

Bad Reasons

- Pimps: I’ve only ever met two pimps in my life. Neither of those times was that great of an experience. The pimps were not anywhere near as entertaining as the flamboyant pimps you see in movies from the '70s. They were more like the pimps from Taken.

- Fiends: What’s happening right now?

- Riots (not rallies): No, thank you. But you have fun at your riot full of pimps and fiends. That’s ten good and three bad. California seems okay.

- This.

- Just.

- Keeps.

- On.

- Getting.

- Worse.

- And.

- Worse.

- He was shot five times on December 1, 1994, the night before the sentencing. He rolled himself right TF into the courtroom the next day.

- The first five albums Death Row released: Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, Snoop’s Doggystyle, the soundtrack for Above the Rim, the soundtrack for Murder Was the Case, and Tha Dogg Pound’s Dogg Food.

- I can’t think of four actors who had a better back-to-back-to-back run, seriously.

- I meant this generally—the big videos, the budgets, all that—but in this case it’s also specific: Puff re-created the desert scene from "California Love" in his "Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down" video. He just replaced the Mad Max cars with a very expensive one for him and Mase.

- The original version, I mean. Not the 2011 remake. The 2011 remake was a real chore, the one clear exception being Miles Teller as Willard.

He wasn’t nearly as complex as Chris Penn, but he was still a total gem.

This is an excerpt from Shea Serrano's new book, The Rap Year Book: The Most Important Rap Song From Every Year Since 1979, Discussed, Debated, and Deconstructed, which is available now. Reprint courtesy of Abrams Books.